The small motorboat anchors in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay. Shrieks of wintering birds assault the vessel’s five crew members, all clad in bright orange flotation suits. One of the crew slowly pulls a rope out of the water to retrieve a plastic tube, about the length of a person’s arm and filled with mud from the bottom of the bay. As the tube is hauled on board, the stench of rotten eggs fills the air.

“Chesapeake Bay mud is stinky,” says Sairah Malkin, a biogeochemist at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science in Cambridge who is aboard the boat. The smell comes from sulfuric chemicals called sulfides within the mud. They’re quite toxic, Malkin explains.

Malkin and her team venture out onto the bay every couple of months to sample the foul muck and track the abundance of squiggling mud dwellers called cable bacteria. The microbes are living wires: Their threadlike bodies — thinner than a human hair — can channel electricity.

Cable bacteria use that power to chemically rewire their surroundings. While some microbes in the area produce sulfides, the cable bacteria remove those chemicals and help prevent them from moving up into the water column. By managing sulfides, cable bacteria may protect fish, crustaceans and other aquatic organisms from a “toxic nightmare,” says Filip Meysman, a biogeochemist at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. “They’re kind of like guardian angels in these coastal ecosystems.”

Now, scientists are studying how these living electrical filaments might do good in other ways. Laboratory experiments show that cable bacteria can support other microbes that consume crude oil, so researchers are investigating how to encourage the bacteria’s growth to help clean up oil spills. What’s more, researchers have shown that cable bacteria could help slash emissions of a potent greenhouse gas — methane — into the atmosphere.

There’s plenty of evidence that cable bacteria exert a strong influence over their microbial neighbors, Meysman says. The next step, he says, is to figure out how to channel that influence for the greater good.

Electric life

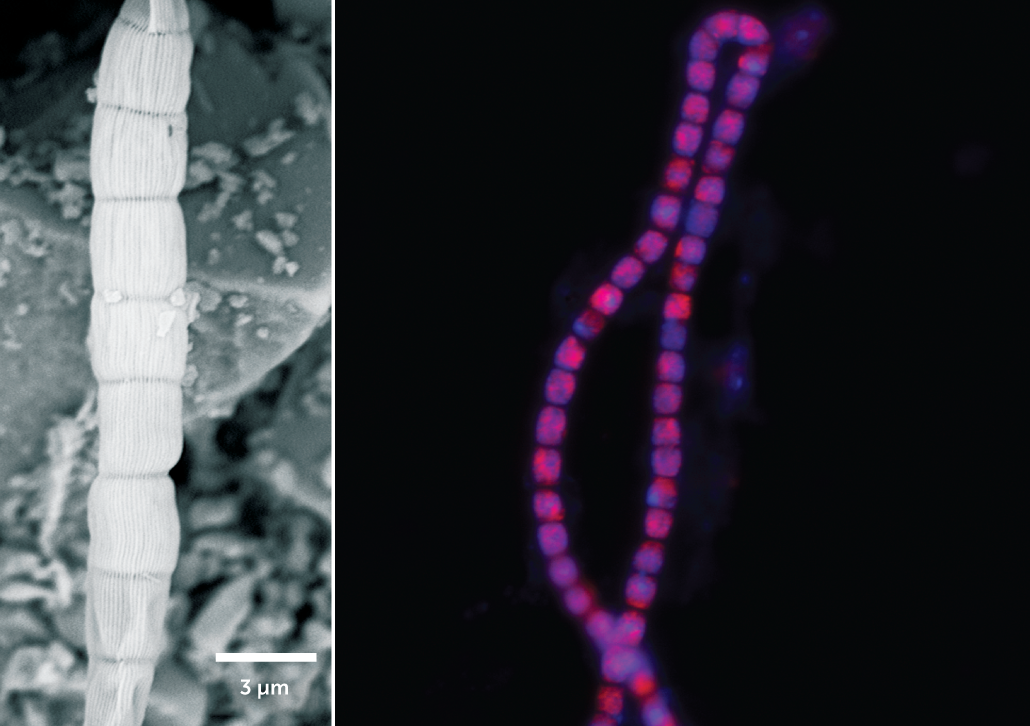

Under the microscope, cable bacteria resemble long sausage links. Their multicellular bodies can grow up to 5 centimeters long. Embedded in the envelope of each cell are parallel “wires” of conductive proteins, which the bacteria use to channel electrons. According to Meysman, the wires are more conductive than the semiconductors found in electronics.

About a decade ago, a team of scientists first discovered cable bacteria, in sediment collected from the bottom of Denmark’s Aarhus Bay. Since then, cable bacteria have been found on at least four continents, in streams, lakes, estuaries and coastal environments. “Name me a country, and I’ll show you where the cable bacteria are,” Meysman says.

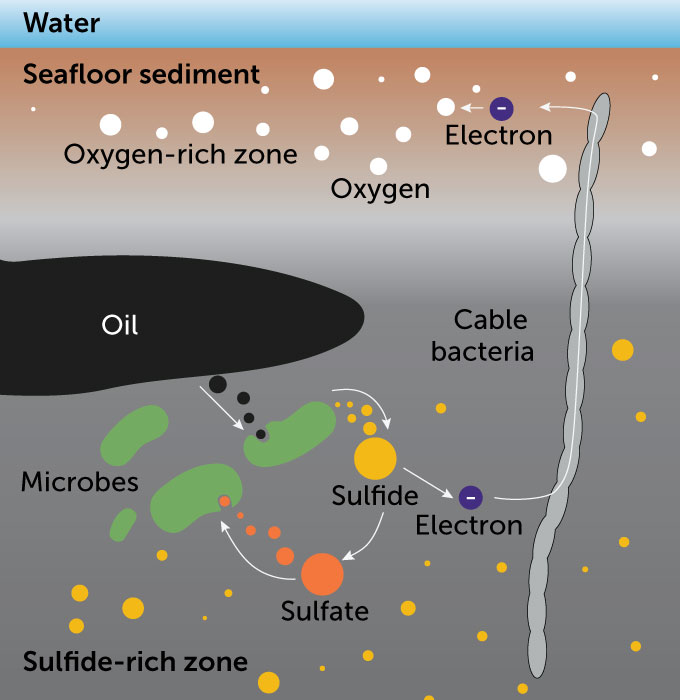

Most often, cable bacteria nestle shallow in the sediment, with one end positioned near the surface where there is oxygen and the other end plugged into deeper, sulfide-rich zones. Using their filamentous bodies as electrical conduits, cable bacteria snatch electrons from sulfides on one end and off-load them to oxygen — an eager electron acceptor — at the other, says Nicole Geerlings, a biogeochemist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. Similar to how batteries charge and release energy by transferring electrons between an anode and cathode, cable bacteria power themselves by channeling electrons, she says. “The electron transport gives [cable bacteria] energy.”

This unique lifestyle allows cable bacteria to survive in an environment that many organisms could not endure.

Toxic fire wall

In 2015, Malkin, Meysman and colleagues reported that cable bacteria may help to counteract the onset of euxinia — a fatal buildup of sulfides in oxygen-starved bodies of water. Euxinia can trigger mass die-offs of fish, crustaceans and other aquatic life.

The lethal phenomenon can occur after fertilizers or sewage are washed into the sea or lakes. That flow of nutrients can trigger algal blooms. When those nutrients are depleted, the blooms die, and large quantities of organic matter sink and accumulate on the sediment. Microbes then decompose the dead material, devouring much of the oxygen in the surrounding water in the process. When oxygen levels become critically low, sulfides may begin to leak from the sediment into the water, giving rise to euxinia.

While studying cable bacteria in a brackish body of water in the Netherlands, Malkin and colleagues discovered a thin layer of rust coating the lake’s bottom. As the cable bacteria pulled electrons from sulfides, converting the noxious chemicals into less-harmful sulfates, the water within the sediment became more acidic, which dissolved some minerals containing iron. The now-mobile iron percolated upward in the sediment, until it interacted with oxygen to form rust.

This layer of rust could capture sulfides that would otherwise flow into the water, acting as a “fire wall” that could delay euxinia for over a month, or even prevent it altogether, the researchers reported. Even when the cable bacteria’s population dropped, the rust layer persisted, protecting other aquatic creatures from sulfide exposure. The rust may explain why even though instances of nutrient pollution, algal blooms and oxygen depletion are relatively common, reports of euxinia are rare.

Oil cleanup

Some researchers are trying to harness the bacteria’s electrical abilities to tackle another devastating threat to coastal ecosystems — oil spills.

When an oil spill happens in a body of water, booms, skimmers or sorbents are often deployed to limit the spread of hydrocarbons on the surface. But oil may also wash onto beaches, mix with sediments in shallow waters and aggregate onto sinking particles of organic debris, hitching a ride to the seafloor.

Cleaning up oil at the bottom of the sea is a difficult job, says Ugo Marzocchi, a biogeochemist at Aarhus University in Denmark. “I am not aware of a very effective way to remove hydrocarbons from the seafloor,” he says. “In inland freshwater systems, what is generally done is to dig out the sediments,” he says, an expensive strategy that would be even more costly at sea.

Some soil-dwelling microorganisms can use hydrocarbons to fuel their metabolism, and researchers have been studying how some of these oil burners might assist in the cleanup of contaminated sediments. But as they break down hydrocarbons, the microbes generate those concerning sulfides, which are detrimental to the microbes’ own survival, Marzocchi says. In other words, the microbes can help clean up the oil for only so long before they’re overwhelmed by their own toxic waste.

Cable bacteria might be just the solution, Marzocchi thought. In 2016, researchers reported finding evidence of the electrical microbes in a tar oil-contaminated groundwater aquifer in Germany. Knowing that cable bacteria could occupy sediments contaminated with hydrocarbons, Marzocchi and colleagues reasoned that these bacteria might be able to assist oil-burning microbes and accelerate oil cleanup.

The researchers filled several containers with oil-contaminated sediment from Aarhus Bay — which contained naturally occurring oil-eating bacteria. The group then injected a few containers with cable bacteria and monitored the degree of hydrocarbon degradation in all of the containers over seven weeks. By the end of the test, the concentration of alkanes — a type of hydrocarbon — in the sediment with cable bacteria had dropped from 0.125 milligrams per gram of sediment to 0.086 milligrams per gram — a 31 percent drop. That’s 23 percentage points more than the 9 percent decrease in the control samples. Cable bacteria helped accelerate the metabolic activity of their oil-eating neighbors by converting the toxic sulfides into sulfates. The sulfates didn’t harm the oil-eating microbes — in fact, they used the chemicals as fuel.

The researchers are now trying to develop methods to promote cable bacteria growth in the field and see if it’s possible to enhance their effect on oil degradation. One catch is that in oil-contaminated sediment, oxygen is quickly used up by the microbes that break down hydrocarbons. That’s a problem since cable bacteria need access to oxygen. Salts that slowly release oxygen or nitrate — which cable bacteria can use in place of oxygen — might help spur the electrical organisms’ growth at oil spills. But more work is needed to identify the right chemical components and dosage, Marzocchi says.

Meanwhile, scientists are investigating how cable bacteria might help reduce emission of another hydrocarbon — one that accumulates in the sky.

Methane at the root

Colorless, odorless methane is the simplest hydrocarbon (SN: 8/15/20, p. 8). It consists of a single carbon atom attached to a quartet of hydrogen atoms. And it’s a potent greenhouse gas — more than 25 times as effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

One major source of methane is rice paddies (SN: 9/25/21, p. 16). During the growing season, rice farmers typically flood their fields to help stave off weeds and pests. Methane-producing microbes — aptly named methanogens — thrive in these waterlogged soils. Paddy-dwelling methanogens are so prolific that rice fields are estimated to generate about 11 percent of all human-induced methane emissions.

But cable bacteria like paddies too. In 2019, Vincent Scholz, a microbiologist at Aarhus University, and colleagues reported that cable bacteria could flourish among the roots of rice plants and several other aquatic plant species.

That discovery inspired the researchers to investigate how the bacteria interact with methanogens in soils that grow rice. The team grew its own rice plants — some potted in soils with cable bacteria, and some without — and monitored methane emissions.

To the researchers’ surprise, adding cable bacteria reduced rice soil methane emissions by 93 percent. In the process of removing electrons from sulfides, the bacteria generate sulfates, which other microbes can use as fuel. These sulfate-consuming microbes outcompeted methanogens for nutrients such as hydrogen and acetate in the rice soils, the researchers found. The results were “quite amazing,” Scholz says, though the effectiveness of the electrical microbes in real rice fields has yet to be tested.

There are signs that cable bacteria are already plugged into real rice paddy soils. After analyzing genetic data collected from rice paddies in the United States, India, Vietnam and China, Scholz and colleagues reported in 2021 the presence of cable bacteria at sites in all four countries. Scholz is in Northern California this summer studying how cable bacteria live in rice fields and whether they’re already impacting methane emissions. He is also exploring ways to introduce cable bacteria to rice fields where they don’t yet exist or enhance the microbes’ numbers in fields where they do.

There is still much to discover about how the wispy electrical conductors influence our world, Malkin says. Back in the Chesapeake Bay, she and colleagues have found that cable bacteria tend to flourish in the spring, a surge that has also been observed in the Netherlands. The findings add to a growing body of work that suggests cable bacteria are opportunistic organisms that interact with their environments in similar ways all around the world.

If cable bacteria are already hard at work across the planet, then a bit of coaxing from researchers may be all it takes to turn the mud-dwelling creatures into the most helpful neighbors that a living thing could ask for.