The internet is rife with advice for keeping the brain sharp as we age, and much of it is focused on the foods we eat. Headlines promise that oatmeal will fight off dementia. Blueberries improve memory. Coffee can slash your risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Take fish oil. Eat more fiber. Drink red wine. Forgo alcohol. Snack on nuts. Don’t skip breakfast. But definitely don’t eat bacon.

One recent diet study got media attention, with one headline claiming, “Many people may be eating their way to dementia.” The study, published last December in Neurology, found that people who ate a diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods like fruits, vegetables, beans and tea or coffee had a lower risk of dementia than those who ate foods that boost inflammation, such as sugar, processed foods, unhealthy fats and red meat.

But the study, like most research on diet and dementia, couldn’t prove a causal link. And that’s not good enough to make recommendations that people should follow. Why has it proved such a challenge to pin down whether the foods we eat can help stave off dementia?

First, dementia, like most chronic diseases, is the result of a complex interplay of genes, lifestyle and environment that researchers don’t fully understand. Diet is just one factor. Second, nutrition research is messy. People struggle to recall the foods they’ve eaten, their diets change over time, and modifying what people eat — even as part of a research study — is exceptionally difficult.

For decades, researchers devoted little effort to trying to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia because they thought there was no way to change the trajectory of these diseases. Dementia seemed to be the result of aging and an unlucky roll of the genetic dice.

While scientists have identified genetic variants that boost risk for dementia, researchers now know that people can cut their risk by adopting a healthier lifestyle: avoiding smoking, keeping weight and blood sugar in check, exercising, managing blood pressure and avoiding too much alcohol — the same healthy behaviors that lower the risk of many chronic diseases.

Diet is wrapped up in several of those healthy behaviors, and many studies suggest that diet may also directly play a role. But what makes for a brain-healthy diet? That’s where the research gets muddled.

Despite loads of studies aimed at dissecting the influence of nutrition on dementia, researchers can’t say much with certainty. “I don’t think there’s any question that diet influences dementia risk or a variety of other age-related diseases,” says Matt Kaeberlein, who studies aging at the University of Washington in Seattle. But “are there specific components of diet or specific nutritional strategies that are causal in that connection?” He doubts it will be that simple.

Worth trying

In the United States, an estimated 6.5 million people, the vast majority of whom are over age 65, are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Experts expect that by 2060, as the senior population grows, nearly 14 million residents over age 65 will have Alzheimer’s disease. Despite decades of research and more than 100 drug trials, scientists have yet to find a treatment for dementia that does more than curb symptoms temporarily (SN: 7/3/21 & 7/17/21, p. 8). “Really what we need to do is try and prevent it,” says Maria Fiatarone Singh, a geriatrician at the University of Sydney.

Forty percent of dementia cases could be prevented or delayed by modifying a dozen risk factors, according to a 2020 report commissioned by the Lancet. The report doesn’t explicitly call out diet, but some researchers think it plays an important role. After years of fixating on specific foods and dietary components — things like fish oil and vitamin E supplements — many researchers in the field have started looking at dietary patterns.

That shift makes sense. “We do not have vitamin E for breakfast, vitamin C for lunch. We eat foods in combination,” says Nikolaos Scarmeas, a neurologist at National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Columbia University. He led the study on dementia and anti-inflammatory diets published in Neurology. But a shift from supplements to a whole diet of myriad foods complicates the research. A once-daily pill is easier to swallow than a new, healthier way of eating.

Earning points

Suspecting that inflammation plays a role in dementia, many researchers posit that an anti-inflammatory diet might benefit the brain. In Scarmeas’ study, more than 1,000 older adults in Greece completed a food frequency questionnaire and earned a score based on how “inflammatory” their diet was. The lower the score, the better. For example, fatty fish, which is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, was considered an anti-inflammatory food and earned negative points. Cheese and many other dairy products, high in saturated fat, earned positive points.

During the next three years, 62 people, or 6 percent of the study participants, developed dementia. People with the highest dietary inflammation scores were three times as likely to develop dementia as those with the lowest. Scores ranged from –5.83 to 6.01. Each point increase was linked to a 21 percent rise in dementia risk.

Such epidemiological studies make connections, but they can’t prove cause and effect. Perhaps people who eat the most anti-inflammatory diets also are those least likely to develop dementia for some other reason. Maybe they have more social interactions. Or it could be, Scarmeas says, that people who eat more inflammatory diets do so because they’re already experiencing changes in their brain that lead them to consume these foods and “what we really see is the reverse causality.”

To sort all this out, researchers rely on randomized controlled trials, the gold standard for providing proof of a causal effect. But in the arena of diet and dementia, these studies have challenges.

Dementia is a disease of aging that takes decades to play out, Kaeberlein says. To show that a particular diet could reduce the risk of dementia, “it would take two-, three-, four-decade studies, which just aren’t feasible.” Many clinical trials last less than two years.

As a work-around, researchers often rely on some intermediate outcome, like changes in cognition. But even that can be hard to observe. “If you’re already relatively healthy and don’t have many risks, you might not show much difference, especially if the duration of the study is relatively short,” says Sue Radd-Vagenas, a nutrition scientist at the University of Sydney. “The thinking is if you’re older and you have more risk factors, it’s more likely we might see something in a short period of time.” Yet older adults might already have some cognitive decline, so it might be more difficult to see an effect.

Many researchers now suspect that intervening earlier will have a bigger impact. “We now know that the brain is stressed from midlife and there’s a tipping point at 65 when things go sour,” says Hussein Yassine, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. But intervene too early, and a trial might not show any effect. Offering a healthier diet to a 50- or 60-year-old might pay off in the long run but fail to make a difference in cognition that can be measured during the relatively short length of a study.

And it’s not only the timing of the intervention that matters, but also the duration. Do you have to eat a particular diet for two decades for it to have an impact? “We’ve got a problem of timescale,” says Kaarin Anstey, a dementia researcher at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

And then there are all the complexities that come with studying diet. “You can’t isolate it in the way you can isolate some of the other factors,” Anstey says. “It’s something that you’re exposed to all the time and over decades.”

Food as medicine?

In a clinical trial, researchers often test the effectiveness of a drug by offering half the study participants the medication and half a placebo pill. But when the treatment being tested is food, studies become much more difficult to control. First, food doesn’t come in a pill, so it’s tricky to hide whether participants are in the intervention group or the control group.

Imagine a trial designed to test whether the Mediterranean diet can help slow cognitive decline. The participants aren’t told which group they’re in, but the control group sees that they aren’t getting nuts or fish or olive oil. “What ends up happening is a lot of participants will start actively increasing the consumption of the Mediterranean diet despite being on the control arm, because that’s why they signed up,” Yassine says. “So at the end of the trial, the two groups are not very dissimilar.”

Second, we all need food to live, so a true placebo is out of the question. But what diet should the control group consume? Do you compare the diet intervention to people’s typical diets (which may differ from person to person and country to country)? Do you ask the comparison group to eat a healthy diet but avoid the food expected to provide brain benefits? (Offering them an unhealthy diet would be unethical.)

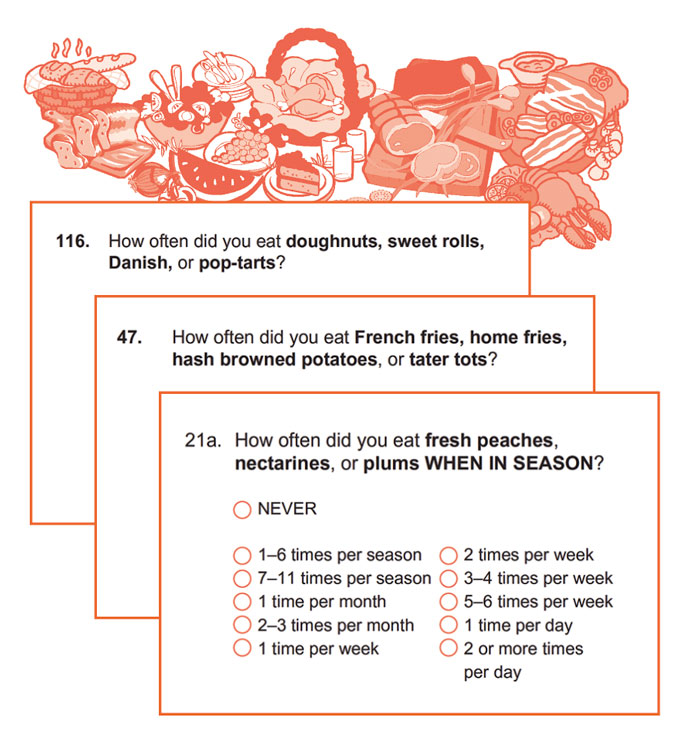

And tracking what people eat during a clinical trial can be a challenge. Many of these studies rely on food frequency questionnaires to tally up all the foods in an individual’s diet. An ongoing study is assessing the impact of the MIND diet (which combines part of the Mediterranean diet with elements of the low-salt DASH diet) on cognitive decline. Researchers track adherence to the diet by asking participants to fill out a food frequency questionnaire every six to 12 months. But many of us struggle to remember what we ate a day or two ago. So some researchers also rely on more objective measures to assess compliance. For the MIND diet assessment, researchers are also tracking biomarkers in the blood and urine — vitamins such as folate, B12 and vitamin E, plus levels of certain antioxidants.

Another difficulty is that these surveys often don’t account for variables that could be really important, like how the food was prepared and where it came from. Was the fish grilled? Fried? Slathered in butter? “Those things can matter,” says dementia researcher Nathaniel Chin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Plus there are the things researchers can’t control. For example, how does the food interact with an individual’s medications and microbiome? “We know all of those factors have an interplay,” Chin says.

The few clinical trials looking at dementia and diet seem to measure different things, so it’s hard to make comparisons. In 2018, Radd-Vagenas and her colleagues looked at all the trials that had studied the impact of the Mediterranean diet on cognition. There were five at the time. “What struck me even then was how variable the interventions were,” she says. “Some of the studies didn’t even mention olive oil in their intervention. Now, how can you run a Mediterranean diet study and not mention olive oil?”

Another tricky aspect is recruitment. The kind of people who sign up for clinical trials tend to be more educated, more motivated and have healthier lifestyles. That can make differences between the intervention group and the control group difficult to spot. And if the study shows an effect, whether it will apply to the broader, more diverse population comes into question. To sum up, these studies are difficult to design, difficult to conduct and often difficult to interpret.

Kaeberlein studies aging, not dementia specifically, but he follows the research closely and acknowledges that the lack of clear answers can be frustrating. “I get the feeling of wanting to throw up your hands,” he says. But he points out that there may not be a single answer. Many diets can help people maintain a healthy weight and avoid diabetes, and thus reduce the risk of dementia. Beyond that obvious fact, he says, “it’s hard to get definitive answers.”

A better way

In July 2021, Yassine gathered with more than 30 other dementia and nutrition experts for a virtual symposium to discuss the myriad challenges and map out a path forward. The speakers noted several changes that might improve the research.

One idea is to focus on populations at high risk. For example, one clinical trial is looking at the impact of low- and high-fat diets on short-term changes in the brain in people who carry the genetic variant APOE4, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s. One small study suggested that a high-fat Western diet actually improved cognition in some individuals. Researchers hope to get clarity on that surprising result.

“I get the feeling of wanting to throw up your hands.”

Matt Kaeberlein

Another possible fix is redefining how researchers measure success. Hypertension and diabetes are both well-known risk factors for dementia. So rather than running a clinical trial that looks at whether a particular diet can affect dementia, researchers could look at the impact of diet on one of these risk factors. Plenty of studies have assessed the impact of diet on hypertension and diabetes, but Yassine knows of none launched with dementia prevention as the ultimate goal.

Yassine envisions a study that recruits participants at risk of developing dementia because of genetics or cardiovascular disease and then looks at intermediate outcomes. “For example, a high-salt diet can be associated with hypertension, and hypertension can be associated with dementia,” he says. If the study shows that the diet lowers hypertension, “we achieved our aim.” Then the study could enter a legacy period during which researchers track these individuals for another decade to determine whether the intervention influences cognition and dementia.

One way to amplify the signal in a clinical trial is to combine diet with other interventions likely to reduce the risk of dementia. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability, or FINGER, trial, which began in 2009, did just that. Researchers enrolled more than 1,200 individuals ages 60 to 77 who were at an elevated risk of developing dementia and had average or slightly impaired performance on cognition tests. Half received nutritional guidance, worked out at a gym, engaged in online brain-training games and had routine visits with a nurse to talk about managing dementia risk factors like high blood pressure and diabetes. The other half received only general health advice.

After two years, the control group had a 25 percent greater cognitive decline than the intervention group. It was the first trial, reported in the Lancet in 2015, to show that targeting multiple risk factors could slow the pace of cognitive decline.

Now researchers are testing this approach in more than 30 countries. Christy Tangney, a nutrition researcher at Rush University in Chicago, is one of the investigators on the U.S. arm of the study, enrolling 2,000 people ages 60 to 79 who have at least one dementia risk factor. The study is called POINTER, or U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk. The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed the research — organizers had to pause the trial briefly — but Tangney expects to have results in the next few years.

This kind of multi-intervention study makes sense, Chin says. “One of the reasons why things are so slow in our field is we’re trying to address a heterogeneous disease with one intervention at a time. And that’s just not going to work.” A trial that tests multiple interventions “allows for people to not be perfect,” he adds. Maybe they can’t follow the diet exactly, but they can stick to the workout program, which might have an effect on its own. The drawback in these kinds of studies, however, is that it’s impossible to tease out the contribution of each individual intervention.

Preemptive guidelines

Two major reports came out in recent years addressing dementia prevention. The first, from the World Health Organization in 2019, recommends a healthy, balanced diet for all adults, and notes that the Mediterranean diet may help people who have normal to mildly impaired cognition.

The 2020 Lancet Commission report, however, does not include diet in its list of modifiable risk factors, at least not yet. “Nutrition and dietary components are challenging to research with controversies still raging around the role of many micronutrients and health outcomes in dementia,” the report notes. The authors point out that a Mediterranean or the similar Scandinavian diet might help prevent cognitive decline in people with intact cognition, but “how long the exposure has to be or during which ages is unclear.” Neither report recommends any supplements.

Plenty of people are waiting for some kind of advice to follow. Improving how these studies are done might enable scientists to finally sort out what kinds of diets can help hold back the heartbreaking damage that comes with Alzheimer’s disease. For some people, that knowledge might be enough to create change.

“One of the reasons why things are so slow in our field is we’re trying to address a heterogeneous disease with one intervention at a time. And that’s just not going to work.”

Nathaniel Chin

“Inevitably, if you’ve had Alzheimer’s in your family, you want to know, ‘What can I do today to potentially reduce my risk?’ ” says molecular biologist Heather Snyder, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association.

But changing long-term dietary habits can be hard. The foods we eat aren’t just fuel; our diets represent culture and comfort and more. “Food means so much to us,” Chin says.

“Even if you found the perfect diet,” he adds, “how do you get people to agree to and actually change their habits to follow that diet?” The MIND diet, for example, suggests people eat less than one serving of cheese a week. In Wisconsin, where Chin is based, that’s a nonstarter, he says.

But it’s not just about changing individual behaviors. Radd-Vagenas and other researchers hope that if they can show the brain benefits of some of these diets in rigorous studies, policy changes might follow. For example, research shows that lifestyle changes can have a big impact on type 2 diabetes. As a result, many insurance providers now pay for coaching programs that help participants maintain healthy diet and exercise habits.

“You need to establish policies. You need to change cities, change urban design. You need to do a lot of things to enable healthier choices to become easier choices,” Radd-Vagenas says. But that takes meatier data than exist now.