Learning the origin of a log headed to a furniture factory would be a first step against deforestation

Artisans carve rosewood at a furniture factory in China’s Jiangsu province in March 2019. Scientists are using forensics to keep endangered rosewood species out of the factories.

Jian Zhong Wang’s home in the southern Chinese city of Nanning is an inviting place. Light spills in through large bay windows, which offer a stunning view of the garden of thick-stemmed banana plants and chest-high cacti. The room is packed with intricately carved furniture: a dining table flanked by eight straight-backed chairs, a coffee table and a settee, plus four armchairs, a desk, a divan and a TV stand. Each piece is made of rosewood.

“Rosewood furniture is part of our great

national culture with over 5,000 years of history,” says Wang, a 60-year-old

retired government official who began collecting rosewood more than two decades

ago. He’s not alone.

The furniture is a major status symbol in China, by far the largest importer of rosewood. A canopy bed can fetch as much as $1 million, and an estimated 30,000 companies in China are involved in the rosewood industry, which generated a domestic revenue of over $22 billion in 2014.

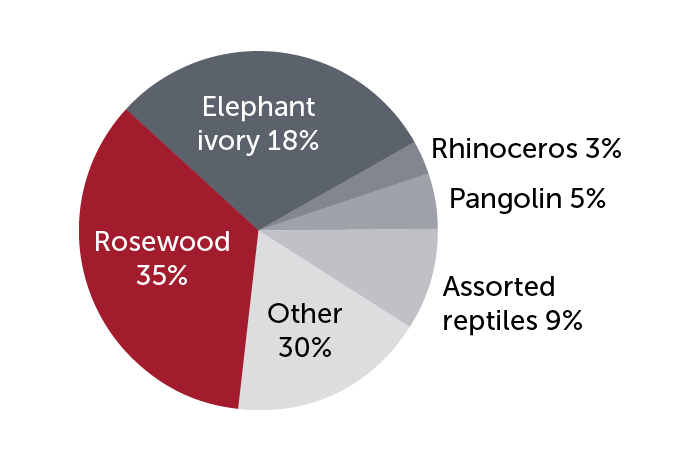

Demand for the beautiful, dark pieces comes at a price. Rosewood is the most trafficked wildlife product in the world based on market value — more than elephant ivory, rhino horns and pangolin scales combined. More than one-third of illegally traded plants and animals seized between 2005 and 2014 were rosewood, according to the World Wildlife Seizures database.

Rosewood is a broad term, referring to

the darkest, mostly uniformly colored hardwoods that come from several genera,

including Dalbergia, Pterocarpus and Millettia. The trees

are found primarily in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America, all areas

experiencing forest loss because of logging and trafficking of the wood.

Because many species

are involved and not all are protected by regulation from overharvesting, identifying

trafficked wood is a challenge. Scientists are trying to help by applying

techniques — including microscopy and chemical and genetic analyses — that

might allow easier identification of wood. The genetic approach, called DNA

barcoding, is being tested for other endangered species as well, including

sharks, elephants and parrots.

Learning the species and origin of

rosewood logs that have been felled will not save the forests. But the hope is

that better identification will allow easier prosecution of traffickers,

discouraging them from taking down more trees.

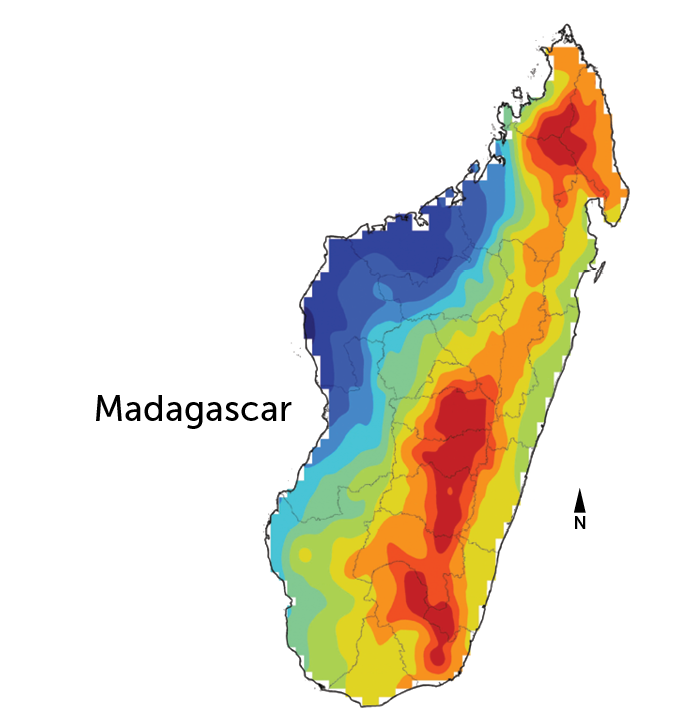

Roots of an industry

Rosewood trees, many of which take centuries to grow to full maturity, are important within their ecosystems. In Madagascar, home to some of the world’s most valuable Dalbergia species, the trees are crucial forest habitats for lemurs. One litter of red variegated lemurs (Varecia rubra) was seen nesting in about 40 large, mature trees in Masoala National Park, according to research published in September 2018 in the American Journal of Primatology. As those trees disappear, local extinctions become a risk. In the arid landscapes of mainland Africa, certain rosewood species, such as Pterocarpus erinaceus, can help protect against fires. The trees also pull nitrogen from the air and improve soil fertility for nearby plants.

Regulatory efforts to protect the world’s rosewood trees have increased, at least on paper. Since 2017, all of the world’s Dalbergia species — more than 300 — as well as some other rosewoods have come under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, an international agreement that protects endangered animals and plants by restricting their trade across borders. Before that, only seven rosewood species were protected by CITES. At the CITES meeting in August, P. tinctorius, an African rosewood that has been harvested heavily in recent years, was added to the list.

Most rosewood

species are classified under CITES Appendix II, which means that trade is

allowed but tightly controlled. Before issuing export permits, the exporting

countries must assess if a tree species has been sustainably and legally

harvested. To determine whether harvesting is sustainable, CITES’ scientific

authority in a given country assesses a species’s population, patterns of

harvest and geographic range.

CITES has only a limited ability to

pressure countries to follow the regulations. “There’s not much the [CITES]

secretariat can do besides giving [countries] a slap on the wrist,” says Naomi

Basik Treanor, who manages the forest policy, trade and finance initiative at

Forest Trends, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit.

Even though trade

restrictions have expanded in recent years, plenty of rosewood still makes its

way out of source countries. Law enforcement officials continue to seize huge

rosewood shipments at ports across the world. From 2017 to mid-2018, close to

200 tons of logs, worth an estimated $50 million, were seized in Hong Kong

alone.

But prosecution is difficult even in the most flagrant cases. In 2014, Singapore authorities seized nearly 30,000 rosewood logs en route to Hong Kong. The logs, which were restricted under CITES, originated in Madagascar. It was one of the largest wildlife seizures in history. Yet in April this year, Singapore’s high court acquitted the trader and ordered the wood returned to him.

Because rosewood enters China via long

and complex trade routes, enforcement is tricky. Along the way, traders can

easily falsify the origin of their logs, or hide illegally harvested logs among

legal species. Customs officials in China check the paper work that accompanies

incoming timber but don’t have the political support or the tools to challenge

potentially false claims. And the country has no laws requiring wood and

furniture companies to check their timber supply chains.

In contrast, the United States,

Australia, Japan and the European Union in recent years passed legislation

requiring companies to ensure that timber entering their supply chains is

legally harvested. Enforcement of such laws remains limited, partly because

identifying the type and origin of wood is not easy.

The United States, for example, has one of the strictest laws prohibiting imports of illegally harvested timber. Yet results of a survey and wood product analysis published July 25 in PLOS ONE show that more than 60 percent of tested wood specimens from major retailers had been wrongly identified. That’s a sign that much of the wood may have been illegally logged and mislabeled at some point in the supply chain.

Ideally, policing

tropical forests would stop the tree cutting way before any rosewood logs reach

foreign markets. But trafficking networks are agile. When a timber supply

dwindles or law enforcement gets serious in one locale, the traffickers move to

another source, usually in another low-income country. With rosewood in

Southeast Asia largely depleted, West Africa now produces an estimated 70

percent or more of the rosewood going into China, Basik Treanor says.

Certain countries, especially in West

Africa, find ways to skirt the CITES regulations. Right now, Sierra Leone,

Ghana and Mali are among the largest exporters of rosewood in the world, says

Susanne Breitkopf, deputy director of forest campaigns for the Environmental

Investigation Agency, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit. But that might not be

true for long.

“It changes year to

year, and even month to month. Rosewood trade is like a virus that keeps

spreading, affecting those with the weakest immune system,” she says. “If one

patient is successfully treated, it immediately jumps on the next, where it can

expand with the least resistance.”

And the Chinese traders tend to tap into

larger criminal networks that capitalize on corruption and other forms of

instability, Basik Treanor says. “The criminal networks don’t care what they’re

trafficking in. It could be humans or drugs or weapons or rosewood.”

Wood forensics

Forensic techniques

have long been used to help identify criminals and ensure the safety of food.

Now the tools are being adapted for use in tree sleuthing, with some victories

for conservationists.

A U.S. case involving Lumber Liquidators

is a model for how governments can use forensics to fight timber trafficking.

The Virginia-based hardwood-flooring company was fined more than $13 million in

2016 for importing illegal wood. The penalty was the largest to date for a

timber-related violation of the Lacey Act, the U.S. law that bans illegally

sourced wood products from entering the country. The company pleaded guilty to

importing illegal Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica) harvested from

forests in eastern Russia. Those forests are protected habitat for the world’s

last remaining Siberian tigers.

The timber originally had been labeled as Welsh oak from Europe, which is legal to import. Proving the wood’s real origins was difficult. U.S. prosecutors turned to Agroisolab, a German-British firm that specializes in stable isotope ratio analysis. The method measures the ratio of different forms, or isotopes, of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sometimes sulfur present in a wood sample. Trees absorb and retain varying levels of these elements depending on soil, rainfall and other environmental factors.

To analyze a sample,

scientists take a cubic centimeter of wood and grind it into a fine powder and

then turn it into a gas for analysis in an isotope ratio mass spectrometer.

Separation of the components based on their electric charges and masses

indicates the ratio of isotopes present, and therefore which geographic region

the wood came from. But as with DNA analysis, there’s got to be a robust

database of tree samples to compare the results against.

“Let’s say I commit a crime and my

fingerprints are all over the place,” says Pete Lowry, a Paris-based botanist

with the Missouri Botanical Garden, a research facility with international

reach. Lowry studies some of the world’s most valuable rosewoods, including

those from Madagascar. “Unless my fingerprint is in a library someplace, no one

is going to know it’s me.”

So Lowry and others

are taking “fingerprints” of the world’s trees. The Lumber Liquidators case was

an early success story. When Agroisolab didn’t have enough reference material

to determine where the company’s oak flooring was from, conservation groups

fanned out and collected tree samples from 50 sites in Siberia for comparison’s

sake. The forensic evidence helped seal Lumber Liquidators’ fate.

To build the

reference databases needed to fight tree crimes, the U.S. government, mainly

via the Forest Service, in the last four years has invested hundreds of

thousands of dollars in WorldForestID. The network of government bodies, labs and nongovernmental

organizations, or NGOs, is creating a library of location-specific wood

samples. Researchers from the Forest Stewardship Council, based in Bonn, Germany,

are collecting leaf and wood samples from around the world and sending them to

London’s Kew Gardens, home of the project’s main library.

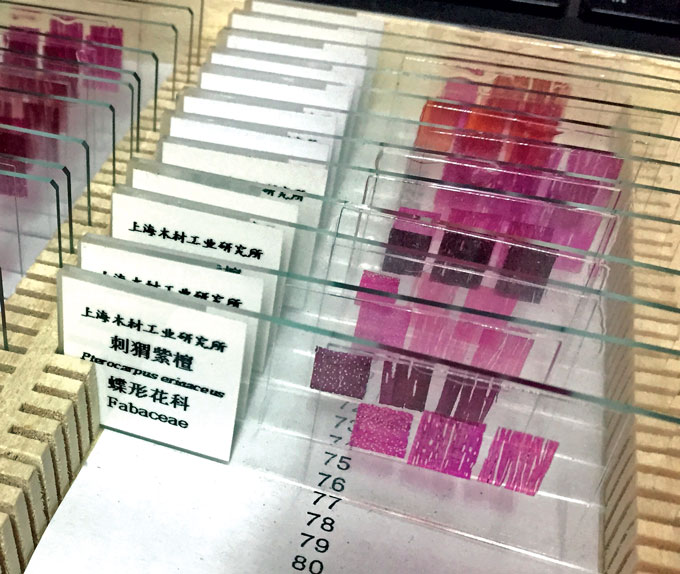

Anatomy lesson

Research happening in Zurich and

Madagascar is more specific to rosewood. Some of the work is dedicated to

low-cost, traditional wood anatomy studies using microscopy. A seasoned

professional usually can tell a wood’s genus from its cell structure and vessel

pattern, but there are few such experts. Great Britain, for example, has only

one.

With microscopy, species-level

identification is hard to pull off. Yet good forest policy requires such

specificity. Outright bans on logging of entire genera, such as Dalbergia,

are unlikely to be approved. So conservationists need to know what can and

can’t be chopped down. Better identification techniques could help determine

which species, if any, can be sustainably harvested.

“It’s surprising, given the value of the woods, that our understanding of them is very poor,” says Alex Widmer, a plant ecological geneticist at ETH Zurich who studies Madagascar Dalbergia. He presented data in July 2018 in Geneva at a CITES meeting showing that at least 12 known Dalbergia species are each, in fact, more than one species. He used DNA barcoding, which identifies a species based on a short strand of mitochondrial DNA.

Tendro Radanielina is a plant geneticist

who has been doing DNA barcoding on rosewood at the University of Antananarivo

in Madagascar since 2018. The technology is spreading to the low-income

countries that are taking the brunt of the tree loss. The challenge is that the

technique requires excellent samples. DNA is easiest to obtain from fresh

leaves, or from a tree’s bark or outer sapwood. But the wood doesn’t always

come that way.

Many logs sit in

stockpiles for years waiting to be exported, or in warehouses waiting to be

used. If the wood is already sawed into planks or made into a finished product,

the DNA is even more degraded and harder to analyze, says Darren Thomas, CEO of

Singapore-based Double Helix Tracking Technologies, a timber verification

company.

Because each method has limitations, and no one method can perfectly identify a piece of wood, scientists cobble together a combination of techniques. Radanielina’s university colleague, Tahiana Ramananantoandro, runs a near-infrared spectroscopy lab that is just beginning to conduct rosewood research. A forestry engineer, she’s worked with scientists in Brazil who are developing a portable device that uses the method to distinguish wood species that look similar under a microscope. In Brazil, the scientists’ concern is big-leaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), which is also protected under CITES but is easily confused with the more plentiful crabwoods and cedars.

Near-infrared spectroscopy involves illuminating

a thin wood sample with near-infrared light. Chemical bonds within the sample

dictate how much light is reflected or absorbed. The result is a characteristic

light spectrum, which Ramananantoandro and other researchers can use to help

identify the wood.

Shifting demand

For now, a world in which all customs officials have easy access to even one wood identification tool is a distant dream. Less than 1 percent of timber traded around the world is subjected to forensic testing, says forest ecologist Pieter Zuidema of Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands. Zuidema leads Timtrace, which provides commercial timber tracking services using both genetic and chemical tracing methods.

“One of the barriers is clearly in the

development of those techniques and the quality they can deliver,” he says.

“Another one is limited knowledge and awareness … and little capacity at

customs and authorities to implement them.”

While forensic science offers a glimmer of hope in the fight against deforestation, the fate of rosewood will depend largely on how well the trade is controlled in China. It will take a cultural and political shift to convince people like Jian Zhong Wang to see these trees as more than beautiful furniture worth collecting.